Your favorite streaming app pings with a notification: new music from an artist who died three years ago. The familiar flutter of excitement clashes with an uncomfortable reality check—technology and industry machinery now conspire to keep voices alive long after their owners have gone silent.

The Posthumous Production Line

Dead artists are releasing more music than ever, creating a strange new category of “living” discographies.

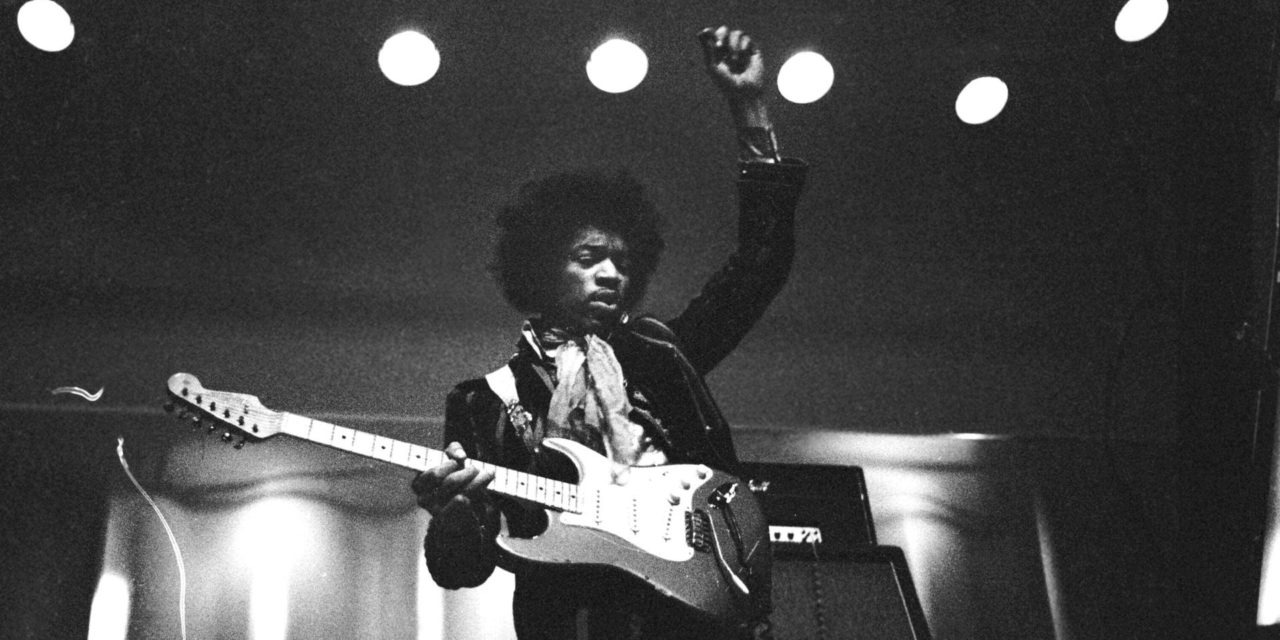

The numbers tell a haunting story. Tupac Shakur has released more albums since his 1996 death than during his brief career. Jimi Hendrix’s posthumous catalog dwarfs his lifetime output. When Mac Miller’s Circles arrived in 2020, fans experienced what music commentators described as a haunting blend of joy and grief—grateful for one more conversation with their lost artist, yet painfully aware it would be the last. This isn’t nostalgia; it’s necromancy with a Billboard chart position.

The Hologram Industrial Complex

Technology transforms deceased performers into touring acts, literalizing the metaphor of voices returning from graves.

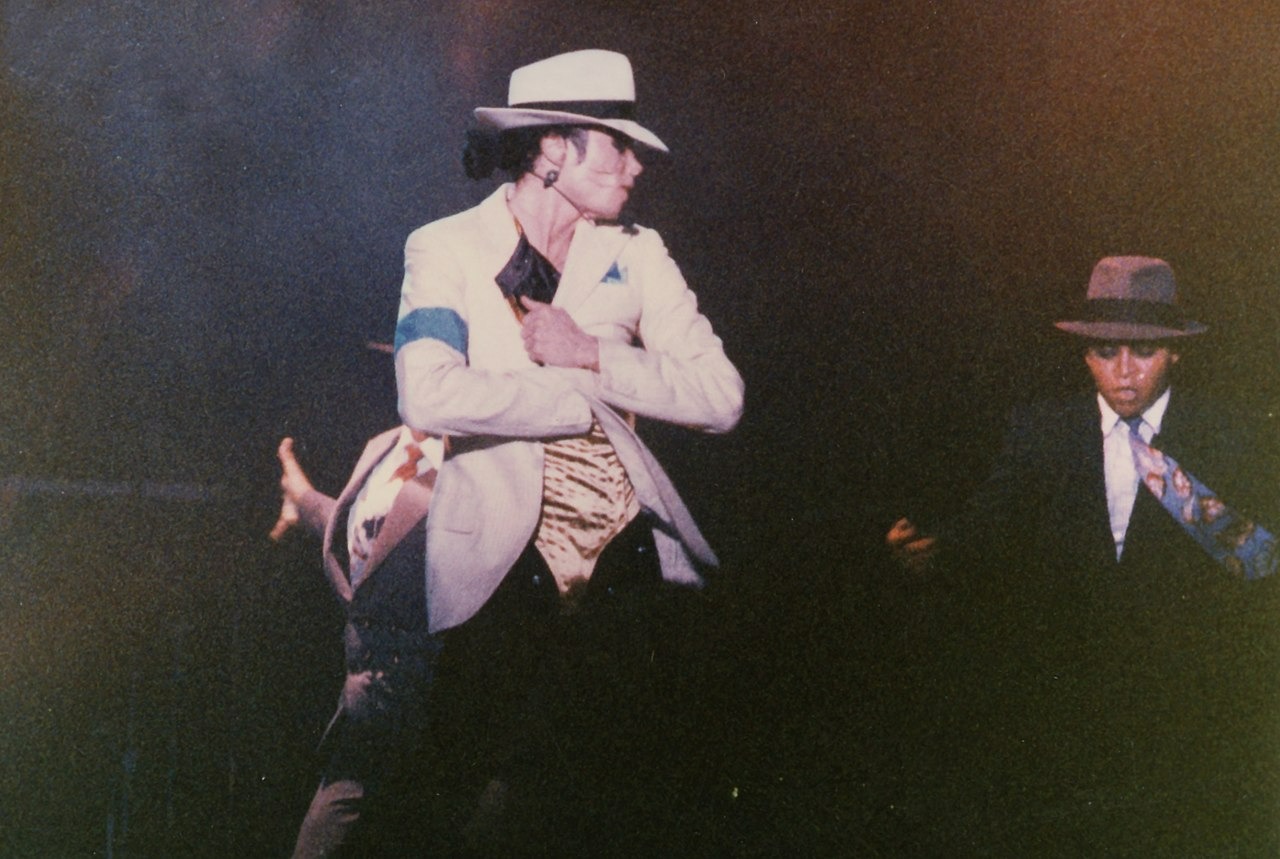

Elvis Presley now “performs” concerts decades after leaving the building for good. Roy Orbison’s hologram sings “Oh, Pretty Woman” to audiences who never saw him breathe. These spectral performances satisfy our collective refusal to let go, but they also raise questions that would make Black Mirror writers nervous. When AI can clone voices and holograms can resurrect stage presence, which version of the artist are you actually mourning?

The Consent Question

Posthumous collaborations and releases often clash with artists’ original intentions, creating ethical minefields for estates and labels.

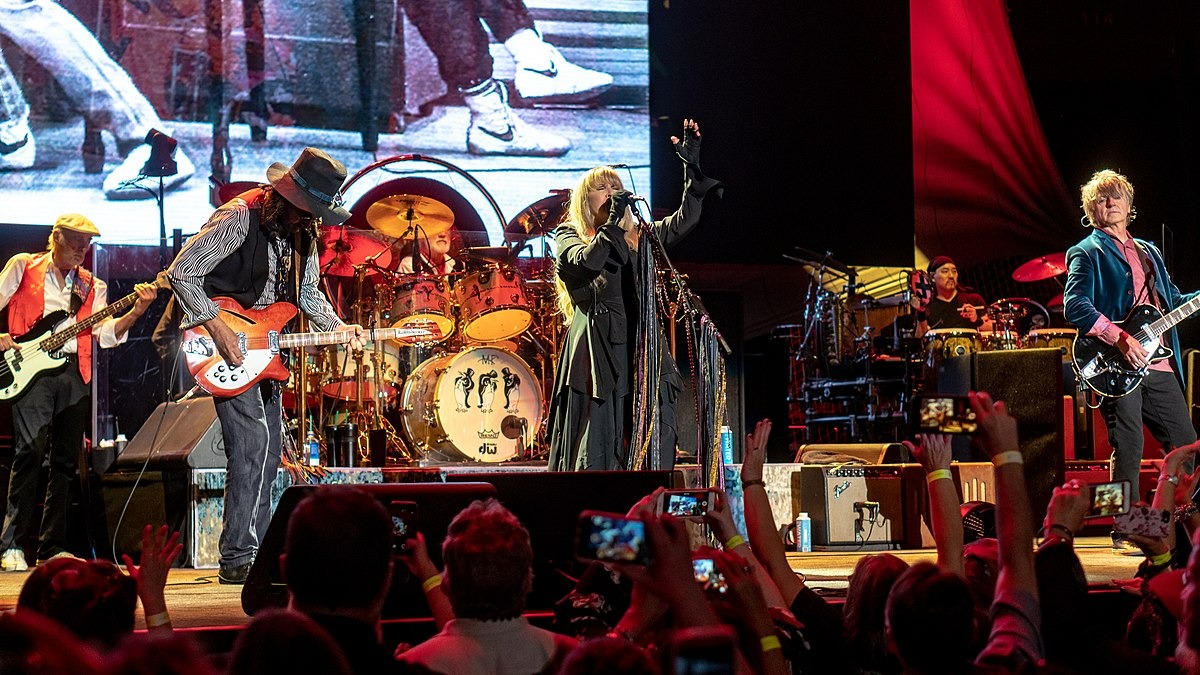

The controversy around Lil Peep and XXXTentacion’s posthumous collaborations exposes the industry’s uncomfortable truth: death transforms artists from creative partners into intellectual property. Commentary on posthumous ethics suggests these releases sometimes damage an artist’s legacy when they stray from the original vision. Meanwhile, Joy Division’s “Love Will Tear Us Apart,” released after Ian Curtis’s suicide, became canonical precisely because its posthumous context deepened every lyric.

Navigating the Afterlife Economy

Fans must develop new critical frameworks for consuming music that exists in ethical gray areas.

Your streaming habits now require philosophical consideration. Each posthumous album forces a choice between celebrating artistic legacy and potentially enabling exploitation. The key lies in distinguishing between respectful curation—like Queen’s Made in Heaven or John Lennon’s Milk and Honey—and cash grabs assembled from scraps.

Technology will only expand these possibilities, but your discernment as a listener remains the final arbiter of what deserves your emotional investment.