While today’s artists mine personal trauma for streaming algorithms, Roy Orbison transformed genuine heartbreak into operatic masterpieces that still soundtrack solitude decades later. His three-octave range and emotionally charged ballads created something unprecedented: rock songs that felt like classical compositions, built for the darkness of late-night drives and empty rooms. Orbison’s story proves that authentic vulnerability—not manufactured sentiment—creates the kind of lasting impact that survives both tragedy and time.

The Voice That Made Loneliness Beautiful

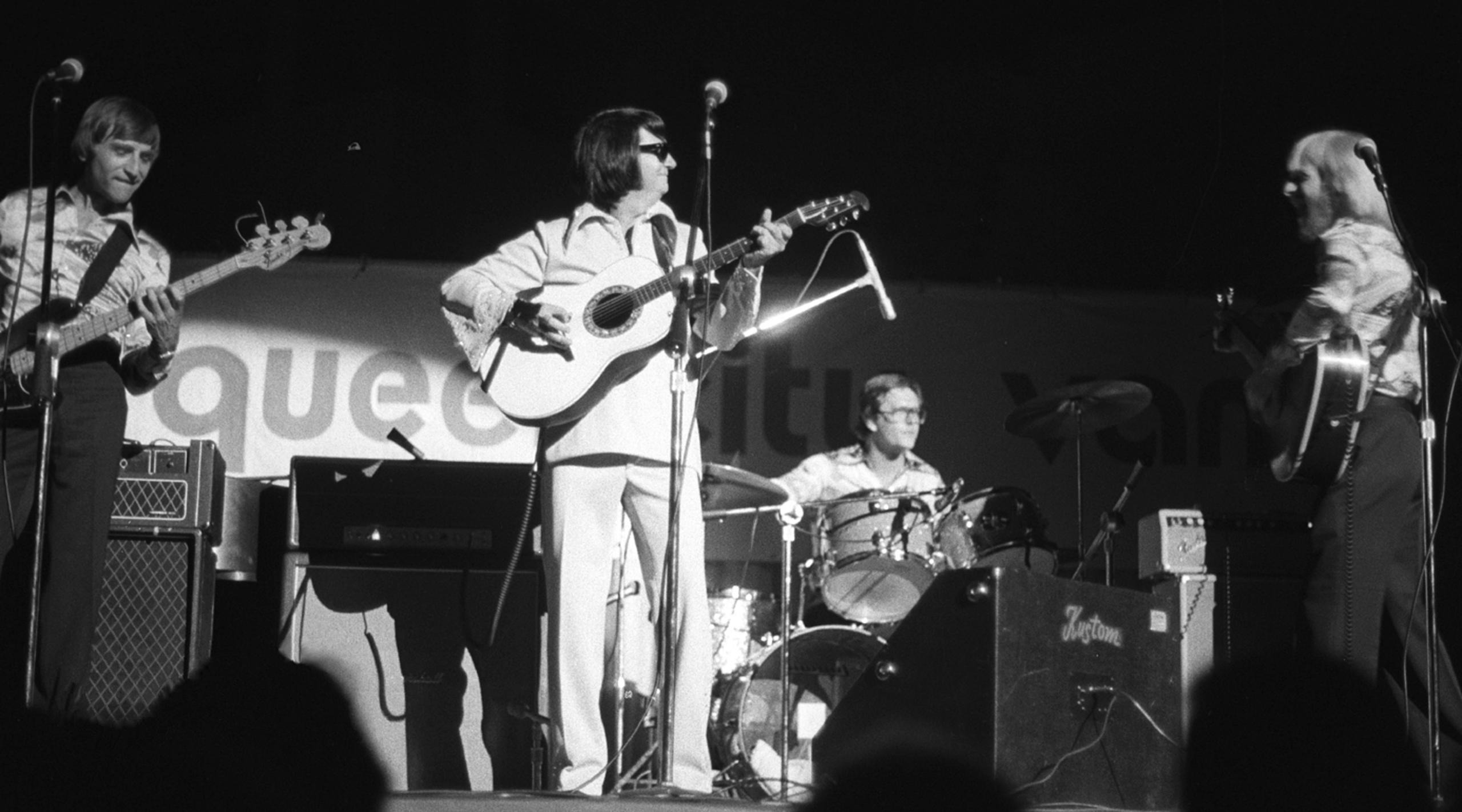

Orbison’s signature sound emerged from technical mastery and genuine emotional depth.

Orbison’s breakthrough hits—“Only the Lonely” (1960), “Crying” (1961), and “In Dreams” (1963)—established him as something entirely different from his rock contemporaries. His soaring, operatic delivery could climb from baritone whispers to falsetto crescendos, often abandoning traditional verse-chorus structures for through-composed epics that followed emotional logic rather than radio formulas. Bruce Springsteen captured it perfectly: “His voice was unearthly.”

These weren’t just songs; they were three-minute operas about heartbreak, delivered by someone who understood the subject intimately.

When Life Became Art’s Cruelest Teacher

Personal devastation in the 1960s deepened Orbison’s artistic vision while derailing his career.

The tragedies that struck Orbison read like cruel fiction:

- His wife, Claudette, died in a 1966 motorcycle accident

- Two sons were lost in a house fire two years later

These devastating events coincided with shifting musical tastes that left his baroque ballad style suddenly unfashionable.

While his contemporaries adapted or faded away, Orbison kept writing, producing the intensely personal 1969 album One of the Lonely Ones—so raw that it was shelved for decades and only released by his family in 2015.

The Comeback That Proved Authenticity Endures

Orbison’s 1980s resurgence demonstrated that genuine artistry eventually finds its audience again.

Orbison’s resurrection began when David Lynch featured “In Dreams” in Blue Velvet (1986), reintroducing his haunting sound to a new generation. The 1988 Traveling Wilburys project with George Harrison, Bob Dylan, Tom Petty, and Jeff Lynne proved his peers still revered his craft.

His final album, Mystery Girl, completed just before his December 1988 death, became the biggest commercial success of his career—featuring “You Got It,” a song that felt both nostalgic and timeless.

Multiple Hall of Fame inductions and a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award followed. Orbison’s real legacy lives in every artist who chooses emotional honesty over algorithmic optimization. In an era when vulnerability gets manufactured for content, his operatic heartbreak reminds us what authentic emotion actually sounds like.