Music shapes our world in weird and wonderful ways. The 1960s stand out as the decade when songs didn’t just entertain—they sparked revolutions. These tracks became cultural battlegrounds where artists and authorities duked it out over what could be said, sung, or suggested.

Ready to explore twenty songs that rattled the establishment? These tracks didn’t just push boundaries—they bulldozed right through them.

12. Tell Laura I Love Her – Ray Peterson (1960)

Ray Peterson’s tear-jerker about a boy who dies in a car race shocked parents everywhere. Tommy enters the competition to win money for his girlfriend’s ring. Spoiler alert: it doesn’t end well. His final words create the song’s haunting chorus that radio stations found too morbid for teenage ears.

Stations across America banned the record faster than you could change a dial. The funny thing? It topped charts anyway. Much like those horror movies parents forbid teens to watch (only making them more appealing), the song’s forbidden status just made kids want it more. Music historian Ken Barnes notes this track “became the teenage tragedy anthem nobody wanted but everybody needed.”

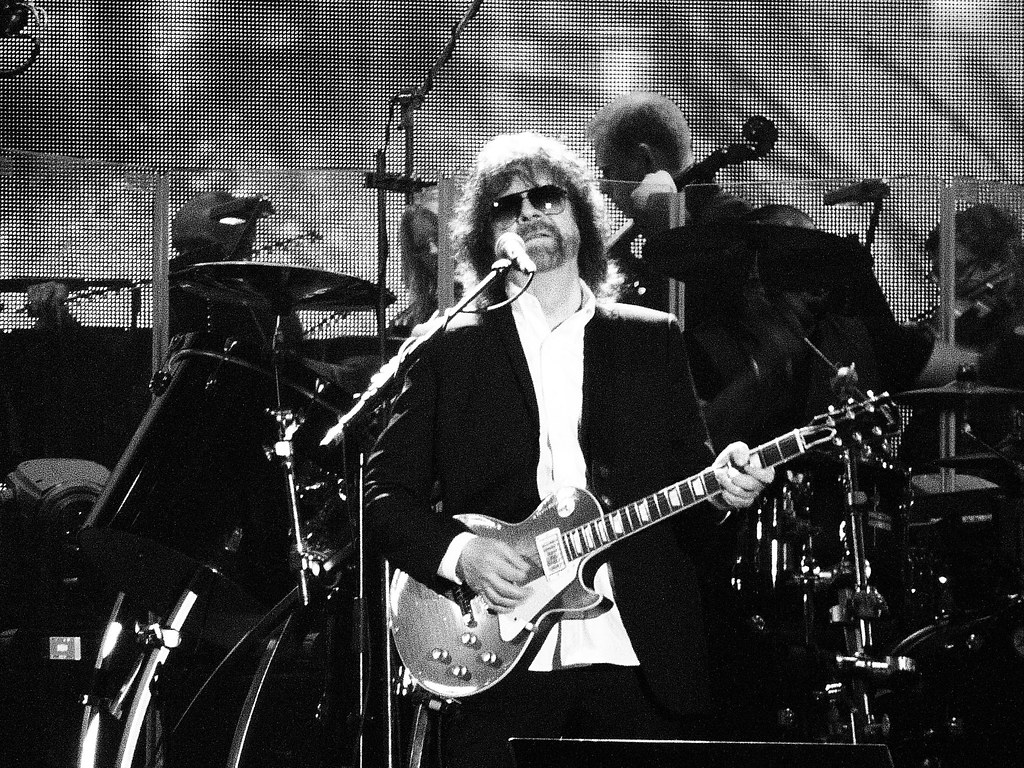

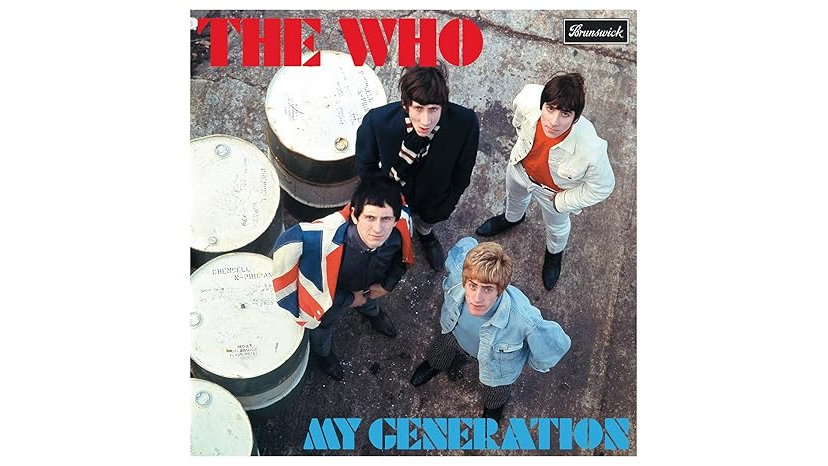

11. My Generation – The Who (1965)

By 1965, kids and parents might as well have been speaking different languages. The Who’s anthem captured this disconnect with a simple declaration: “Hope I die before I get old.” Roger Daltrey’s stuttering delivery wasn’t just artistic—it was downright confrontational.

The BBC clutched their pearls and banned it, worried about offending people with speech impediments. The song climbed to number two anyway. The gap between youth culture and mainstream media had grown wider than the space between a teenager’s headphones and reality. Cultural critic Greil Marcus later observed that this track “wasn’t just rebellion—it was a declaration of independence.”

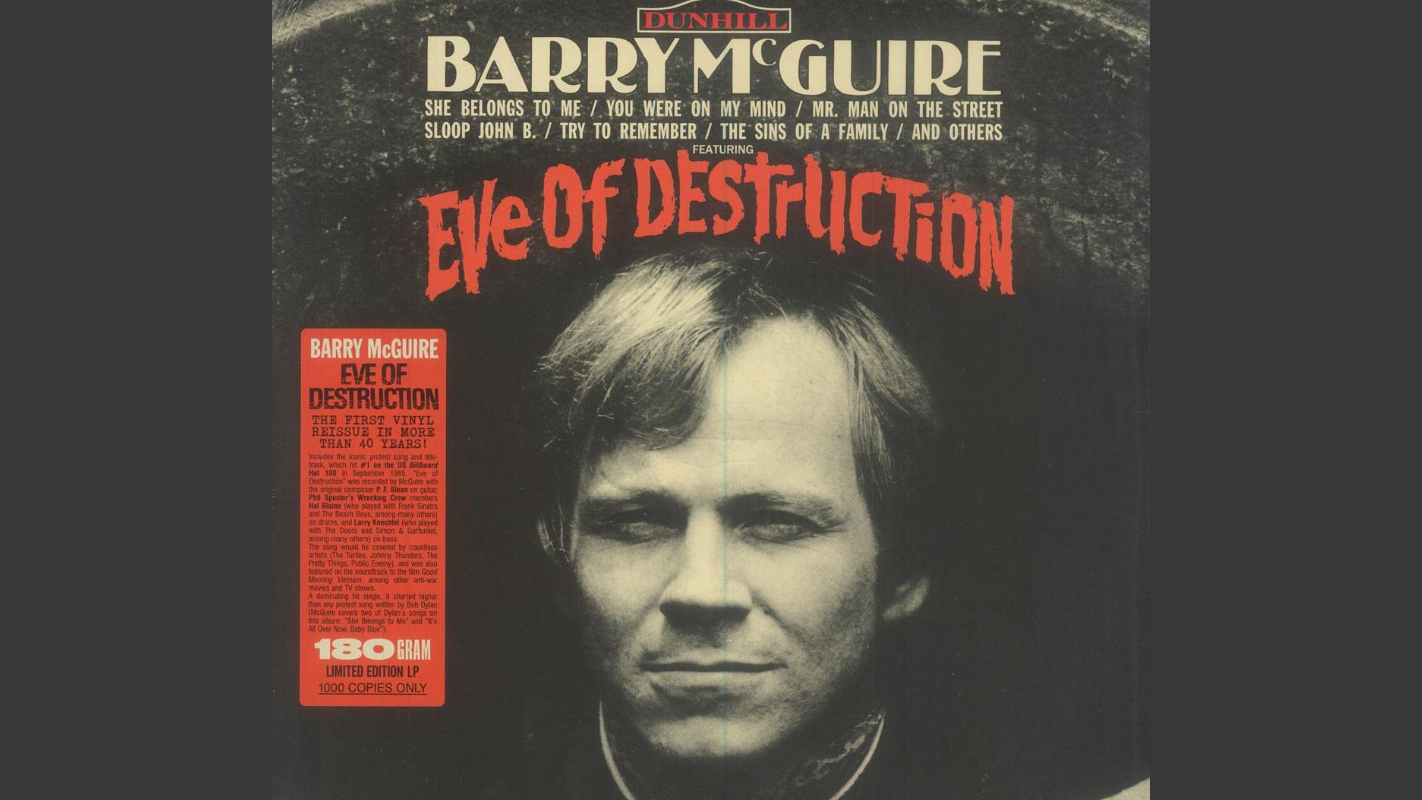

10. Eve of Destruction – Barry McGuire (1965)

As Vietnam escalated, Barry McGuire unleashed a protest bomb that hit every sore spot in American politics. The track confronted war, civil rights, and nuclear fears with zero sugar-coating. Program directors nearly fainted when they heard it.

Bill Drake of RKO General stations specifically hated the line about being “old enough to kill but not for voting.” Many stations blacklisted it as “un-American.” (Heaven forbid young people question authority during wartime!) Despite the ban hammer coming down hard, “Eve of Destruction” topped the Billboard Hot 100. Turns out people actually liked music that said something.

9. Eight Miles High – The Byrds (1966)

The Byrds claimed their 1966 release chronicled a turbulent flight to London. Sure, and “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” was just about a drawing, right? Radio stations didn’t buy it either. The track became a casualty in America’s growing panic about drug culture.

Roger McGuinn’s guitar work borrowed from jazz saxophonist John Coltrane, creating sounds rock hadn’t explored before. His 12-string Rickenbacker guitar wove patterns like a master weaver creating an intricate tapestry—beautiful, complex, and impossible to recreate. Music journalist Richie Unterberger later crowned it “the first bona fide psychedelic rock classic,” officially marking the moment rock music got weird (in the best possible way).

8. A Day in the Life – The Beatles (1967)

“Sgt. Pepper’s” represented The Beatles’ transformation from cute moptops to serious artists. The album’s final track combined John’s dreamlike verses with Paul’s bouncy middle section. The BBC immediately spotted trouble in the line “I’d love to turn you on.”

Officials banned it faster than you could say “moral panic.” The Beatles insisted there weren’t any drug references. Cultural historian Jonathan Gould pointed out the generational disconnect: “Authorities heard drug promotion where young listeners heard poetry about awakening consciousness.” The song became even more famous for being forbidden—a pattern that repeated throughout the decade.

7. Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds – The Beatles (1967)

Another “Sgt. Pepper’s” track sparked similar outrage with its kaleidoscopic imagery. The song’s initials—L.S.D.—didn’t help its case with authorities. John Lennon maintained it came from his son Julian’s drawing of a classmate named Lucy, a defense that convinced approximately nobody at the BBC.

The production created a sonic wonderland matching the surreal lyrics. George Martin’s studio wizardry included flanging, ADT, and other effects that disoriented listeners in delightful ways. The song demonstrated how recording technology had become an instrument itself—capable of creating sounds nobody had heard before.

7. Mississippi Goddam – Nina Simone (1964)

While white artists dipped their toes in controversy, Nina Simone dove headfirst into the raging waters of civil rights. Her response to the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing abandoned the polite approach of earlier protest music. The title alone guaranteed trouble.

Southern states banned it immediately. Some radio stations returned promotional copies broken in half. Despite limited airplay, the song became an anthem for activists. Simone later said, “I wore that title like a badge,” proving sometimes the most powerful statements come with the highest costs.

6. I Feel Like I’m Fixing to Die Rag – Country Joe and the Fish (1965)

As body counts from Vietnam rose, Country Joe McDonald crafted a sardonic response that weaponized humor against war propaganda. The song’s irreverent tone and infamous “fish cheer” earned it an instant ban from family-friendly television.

The song spread through campuses like wildfire despite limited airplay. Its biting chorus asked the question many young men facing the draft couldn’t avoid: “What are we fighting for?” The track became a protest earworm—irritating to authorities but impossible to silence once heard. At Woodstock, when Country Joe performed it for half a million people, the government realized music had become as powerful as any political speech.

5. Fortunate Son – Creedence Clearwater Revival (1969)

As the decade closed, Creedence Clearwater Revival delivered perhaps the most enduring anti-war statement in American music. John Fogerty’s growling vocals pointed out who actually fought wars—and who didn’t. “It ain’t me, I ain’t no senator’s son” resonated with working-class kids facing draft notices.

Conservative stations avoided playing it, considering the critique unpatriotic. Yet the song connected with millions who noticed the same uncomfortable pattern. Unlike many protest songs that faded with their moment, “Fortunate Son” lives on decades later. When politicians use it at rallies, the irony reaches levels that would make Alanis Morissette blush.

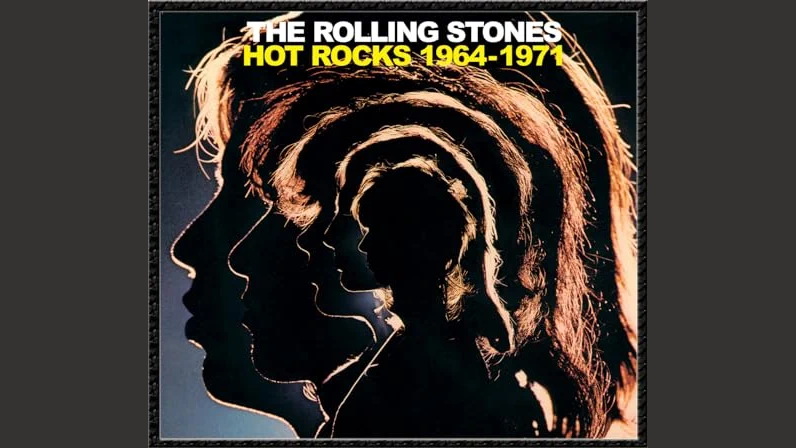

4. Let’s Spend the Night Together – The Rolling Stones (1967)

While protest dominated headlines, songs challenging sexual norms faced equally fierce resistance. The Rolling Stones’ straightforward proposition shocked a broadcasting world still pretending teenagers didn’t have hormones. The BBC clutched their collective pearls and banned it outright.

The real drama happened on American TV. “The Ed Sullivan Show” demanded they change the lyrics to “let’s spend some time together.” Mick Jagger agreed, then rolled his eyes dramatically while singing the sanitized version. His eye-roll became the eye-roll heard ’round the world—like a teenager being forced to wear a suit to a family dinner but finding subtle ways to rebel anyway. The performance showed how meaningless censorship had become.

3. Light My Fire – The Doors (1967)

The Doors created their own television censorship drama months later on the same show. Producers demanded Jim Morrison change “girl, we couldn’t get much higher” before going live. He agreed backstage, then sang the original lyrics anyway. Sullivan’s face probably matched the color of the “On Air” sign.

The band’s permanent ban from the show became a badge of honor in rock circles. Producer Paul Rothchild defended Morrison’s decision: “It wasn’t just childish rebellion—it was defending artistic integrity.” The incident highlighted rock’s growing confidence. Artists no longer felt grateful just to be invited to mainstream platforms. They arrived with their own terms and values.

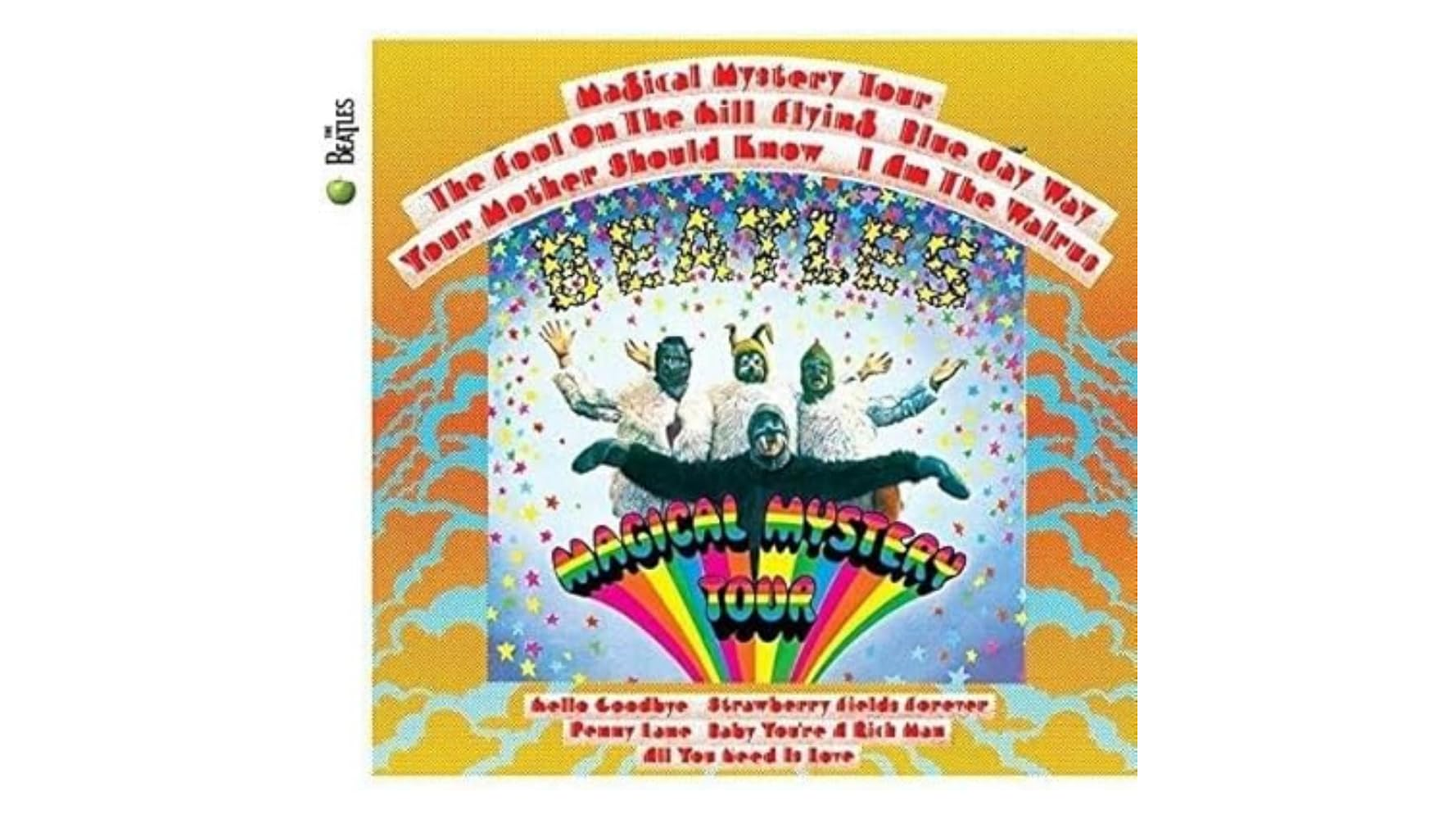

2. I Am the Walrus – The Beatles (1967)

By late 1967, John Lennon had grown tired of people overanalyzing Beatles lyrics. His response? A delightfully nonsensical song designed to confuse anyone trying to find deeper meaning. “Let the English teachers wrestle with this one,” he reportedly said with a mischievous grin.

The BBC still found reason to ban it—the line “you’ve been a naughty girl, you let your knickers down” apparently threatened the very fabric of society. Lennon assembled random images and phrases like a madcap chef throwing ingredients into a pot without measuring—semolina pilchard, eggman, yellow matter custard—creating something weirdly delicious despite (or because of) the strange combination. The song proved sometimes the most rebellious act is refusing to make sense in a world obsessed with logic.

1. Street Fighting Man – The Rolling Stones (1968)

The Rolling Stones released this powder keg during 1968’s global eruptions of protest. Jagger and Richards captured the revolutionary energy while acknowledging its limitations. “What can a poor boy do except sing in a rock and roll band?” became the honest question many musicians asked themselves during political crisis.

Chicago’s WCFL banned it during the Democratic Convention, fearing it might inspire more violence. Keith Richards created its distinctive sound by recording acoustic guitars and processing them to sound electric. The technique mirrored the song’s message—working within limitations while creating the illusion of greater power. Like protesters whose only weapons were their voices, the song found strength in creative adaptation rather than brute force.