The Golden Age of animation wasn’t all Mickey Mouse and Bugs Bunny. Between 1930 and 1950, dozens of studios cranked out experimental shorts that pushed boundaries, tested limits, and occasionally traumatized kids in ways that would make modern parents reach for the remote. These forgotten gems reveal an industry willing to get weird, dark, and surprisingly subversive—long before anyone worried about focus groups or cultural sensitivity committees.

12. The Sunshine Makers (1935)

The Sunshine Makers starts innocent enough: red-dressed gnomes bottle sunlight and convert it into milk to spread joy. Their enemies? Blue goblins living in swamps, singing “We’re happy when we’re sad. We’re always feeling bad.” Sounds wholesome, right? Wrong. The gnomes literally wage war on melancholy, using military tactics to force happiness on unwilling creatures. Modern critics have called it animated genocide—cheerful fascists bombing depression out of existence. Borden’s dairy company loved the milk metaphor so much they reissued it in 1940 as a commercial, proving that corporate America will sponsor anything that moves product. The cartoon’s disturbing undertones about cultural imperialism and pharmaceutical intervention make it accidentally prophetic about our antidepressant culture.

11. Swing You Sinners! (1930)

Bimbo the dog gambles, gets chased by literal demons, and experiences what can only be described as a bad acid trip—except this was 1930, so audiences just called it “surreal.” The animation morphs constantly: skeletons dance, graves open, and reality bends like someone spiked the animator’s coffee with peyote. This short pioneered the “anything can happen” school of animation that Disney would later sanitize into singing teapots. The rubber-hose animation style reaches peak weirdness here, with characters stretching and distorting in ways that suggest the animators were having more fun than anyone in the audience.

10. The Hole Idea (1955)

Professor Calvin Q. Calculus invents a portable hole—literally a hole you can carry around and use to break into anywhere. His wife uses it for housework, criminals steal it for bank heists, and eventually the military gets involved because of course they do. This Warner Bros. short won an Oscar, probably because Academy voters appreciated Jones’ ability to turn Cold War paranoia into slapstick. The portable hole becomes a metaphor for nuclear power: incredibly useful until everyone has one and civilization collapses. Anyone who’s watched politicians debate emerging technology will recognize this exact panic cycle, just with more cartoon physics.

9. Peace on Earth (1939)

Hugh Harman directed this Oscar-nominated short about woodland creatures living in the ruins of human civilization after we’ve destroyed ourselves in war. They find human artifacts—guns, helmets, Christmas decorations—and piece together our violent history. The squirrels literally read from a Bible while standing in bombed-out churches. This isn’t subtle anti-war messaging; it’s animated despair wrapped in holiday packaging. MGM marketed this as family entertainment, apparently believing that children needed to contemplate humanity’s self-destructive tendencies between cartoon gags. The animation quality rivals Disney’s best work, making the existential dread even more unsettling.

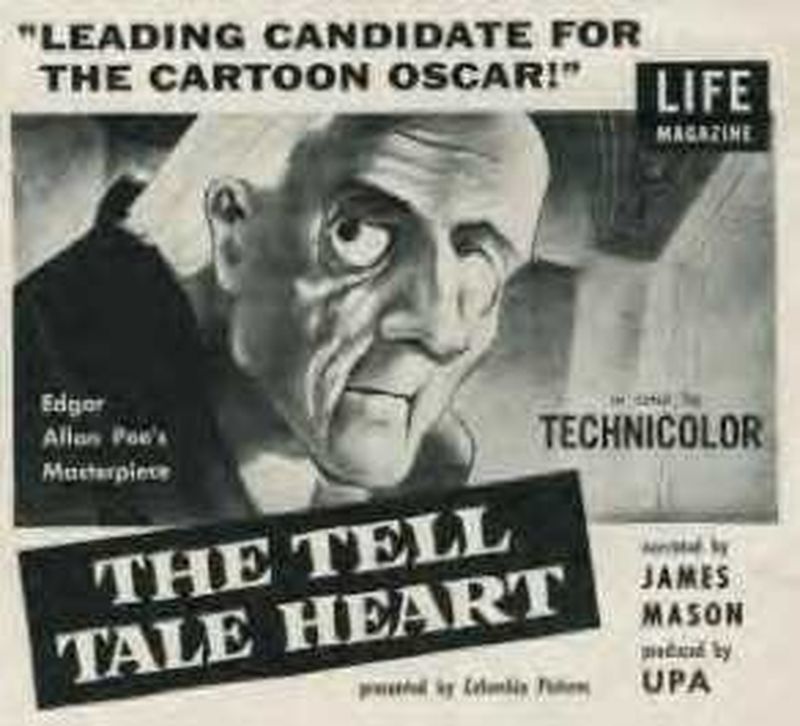

8. The Tell-Tale Heart (1953)

This Academy Award winner proves that animation could handle serious literature without singing mice. James Mason narrates Poe’s classic tale of guilt and madness while abstract visuals represent the protagonist’s deteriorating mental state. The beating heart becomes a visual metaphor rendered in stark, modernist imagery that wouldn’t look out of place in a contemporary art gallery. UPA stripped away cartoon conventions—no anthropomorphic animals, no comic relief, just pure psychological horror. The result feels less like a cartoon and more like animated therapy for people with serious trust issues.

7. What’s Opera, Doc? (1957)

Elmer Fudd becomes a Viking warrior hunting “the wabbit” in this condensed version of Wagner’s “Ring of the Nibelungs.” Bugs Bunny appears in drag as Brunhilde, and what follows is the most culturally literate 7 minutes in cartoon history. Jones crammed an entire opera into cartoon length without losing the emotional weight of the original. The finale—where Elmer believes he’s killed Bugs—contains genuine pathos rare in comedy. This short regularly appears on critics’ lists of the greatest cartoons ever made, proving that high art and rabbit season aren’t mutually exclusive.

6. The Dot and the Line: A Romance in Lower Mathematics (1965)

Based on Norton Juster’s book, this Oscar winner tells the story of a straight line who falls in love with a dot, but she’s attracted to a wild, chaotic squiggle instead. The line learns to bend and curve, becoming more complex and interesting to win her affection. It’s essentially a mathematical coming-of-age story that manages to make geometry emotionally compelling. Chuck Jones directed this masterpiece of abstract storytelling, proving that animation could handle concepts beyond talking animals. The minimal narration by Robert Morley adds British sophistication to what could have been a simple educational film.

5. The Pink Panther (1964)

This Oscar-winning short introduces the Pink Panther not as a jewel but as a mischievous character tormenting a painter trying to paint a house blue. The panther keeps changing it to pink, leading to escalating visual gags that showcase the character’s silent-comedy genius. DePatie-Freleng Enterprises created this as a title sequence for the Blake Edwards film, then expanded it into a standalone cartoon. The jazz score by Henry Mancini became more famous than most pop songs, proving that cartoon music could transcend its medium. The Pink Panther’s wordless comedy influenced decades of animated characters who communicate through attitude rather than dialogue.

4. Gerald McBoing-Boing (1950)

This Oscar winner tells the story of a boy who speaks only in sound effects instead of words. His parents worry, classmates mock him, but eventually Gerald’s unique talent lands him a radio job. The modernist animation style—all geometric shapes and bold colors—was revolutionary for 1950. UPA challenged Disney’s realistic approach with stylized designs that influenced commercial art for decades. The story celebrates neurodiversity before anyone used that term, suggesting that society should adapt to individuals rather than forcing conformity.

3. Duck Amuck (1953)

An unseen animator torments Daffy Duck by constantly changing his environment, costume, and even his species. The cartoon becomes a meta-commentary on the animation process, with Daffy breaking the fourth wall to protest his treatment. Jones turns animation’s technical aspects—backgrounds, sound effects, camera movements—into comedy elements. The revelation that Bugs Bunny is the sadistic animator provides the perfect punchline to 7 minutes of cartoon philosophy. Film schools teach this short as an example of medium-specific storytelling that couldn’t exist in any other art form.

2. The Unicorn in the Garden (1953)

A man sees a unicorn in his garden and tells his wife, who threatens to have him committed. When she calls the authorities, the unicorn disappears, and she gets taken away instead for believing her husband’s “delusion.” Thurber’s dark humor translates perfectly to UPA’s stylized animation, creating a cautionary tale about trust, communication, and the fine line between sanity and imagination. The cartoon suggests that reality is subjective and that sometimes the crazy person is the one calling others crazy—a theme that resonates differently in our current mental health discourse.

1. Knighty Knight Bugs (1958)

Bugs Bunny and Yosemite Sam battle over a singing sword in King Arthur’s court. The cartoon recycles familiar gags in medieval settings, but the execution is so polished that it won the Academy Award for Best Animated Short. Friz Freleng directed this late-period Looney Tunes entry that proves formula can triumph when the formula is perfect. The singing sword provides an excuse for musical numbers, and Sam’s various medieval disguises showcase voice actor Mel Blanc’s range. This Oscar win remains controversial among animation historians who argue that more innovative cartoons deserved recognition.