Everyone knows the hits. The reverent documentaries have canonized “A Day in the Life” and “Eleanor Rigby” to the point where they’re practically a religion. But beyond the calculated mystique of Beatles mythology lies something far more interesting: the songs that reveal who these four working-class lads were when the spotlight dimmed and the marketing machine wasn’t dictating their every move.

These overlooked tracks are secret handshakes between generations of listeners who understand that sometimes the B-sides reveal more truth than the singles ever could. Like finding the director’s cut of a beloved film, these songs expose the raw edges and unfiltered experimentation that the cultural gatekeepers deemed too weird, too personal, or too honest for mass consumption.

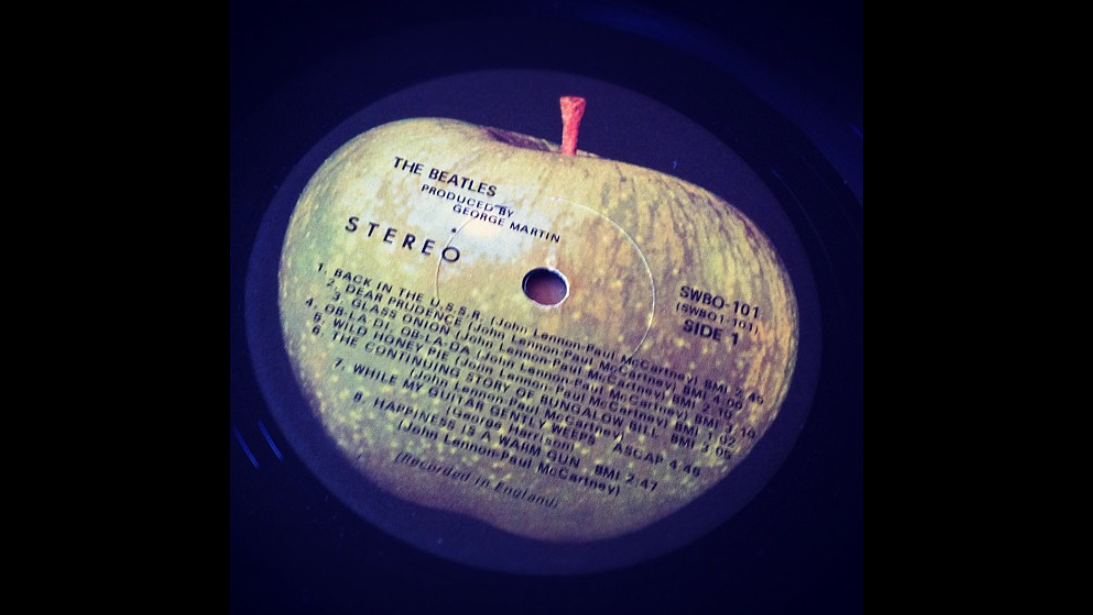

15. Revolution 9

“Revolution 9” functions as the musical equivalent of throwing a Molotov cocktail into a church during Sunday service. “Revolution 9” presents an eight-minute sound collage that sits defiantly on the White Album like an art installation in a shopping mall, daring listeners to question what music even is. While critics dismissed “Revolution 9” as indulgent noise, they missed the point entirely – Lennon wasn’t making a song; he was dismantling the entire concept of popular music.

With Yoko Ono’s influence present, “Revolution 9” incorporated 45 different sound sources into a disorienting soundscape that predicted sample-based music decades before technology caught up. McCartney reportedly fought against its inclusion – the clearest evidence of the band’s fracturing artistic vision. Like Stanley Kubrick’s “2001: A Space Odyssey,” released the same year, “Revolution 9” wasn’t meant to be enjoyed but experienced, challenging the passive consumption model that the record industry depended on.

14. Don’t Pass Me By

Shelved for six years after its 1962 composition, “Don’t Pass Me By” became Ringo’s vindication when Denmark made it a number one hit, proving audiences craved authenticity over the manufactured “cute Beatle” narrative. Composed in 1962, just after joining the band, “Don’t Pass Me By” remained shelved for SIX YEARS while record executives pushed the “cute Beatle” narrative. The fiddle-driven oddity finally escaped onto the White Album in 1968, by which point it felt like a transmission from an alternate timeline where Starr wasn’t just the drummer-shaped punchline to music journalists’ lazy jokes.

The delayed release of “Don’t Pass Me By” speaks volumes about who controlled the Beatles’ narrative. An early demo sold for $16,000 – the price set by collectors who recognized that Ringo’s artistic autonomy was the rarest Beatles artifact of all. While music historians were busy mythologizing Lennon and McCartney, Denmark made “Don’t Pass Me By” a number one hit, proving that audiences were hungrier for authenticity than manufactured perfection.

13. You Like Me Too Much

“You Like Me Too Much” represents the first shots fired in George Harrison’s long war against being typecast as the “quiet one.” Recorded in February 1965 but shuffled between different album releases internationally, this early composition reveals Harrison already pushing against the power structure within the band. The labels couldn’t even decide where to put “You Like Me Too Much” – appearing on “Beatles Six” in America but “Help!” in the UK.

John Lennon’s electric piano drives “You Like Me Too Much” with an insistence that feels like compensation – the musical equivalent of a seasoned actor taking more minor roles to support a promising newcomer. The song’s rejection from the “Help!” film speaks to the corporate machinery’s discomfort with George’s growing voice. Each Harrison composition represented a threat to the carefully cultivated Lennon-McCartney industrial complex, which kept the money flowing and power concentrated.

12. Wild Honey Pie

In just 52 seconds of psychedelic chaos, “Wild Honey Pie” delivers more experimental daring than entire albums by the Beatles’ contemporaries, surviving onto the White Album solely because Pattie Harrison enjoyed it. “Wild Honey Pie” delivers a 52-second blast of psychedelic weirdness that survived onto the White Album solely because Pattie Harrison enjoyed it. In this rare instance, a woman’s musical taste trumped commercial calculation. Created during the band’s meditation retreat in India, “Wild Honey Pie” captures McCartney at his most uninhibited, playing every instrument himself in a burst of creative freedom.

The song “Wild Honey Pie” divides listeners like a musical Rorschach test – either meaningless filler or brilliant deconstruction, depending on whether you believe music should follow rules or break them. Its brevity makes it the sonic equivalent of a Jackson Pollock splatter – a deliberate rejection of conventional structure that forces listeners to confront their expectations. In under a minute, “Wild Honey Pie” delivered what entire psychedelic bands spent careers attempting to achieve.

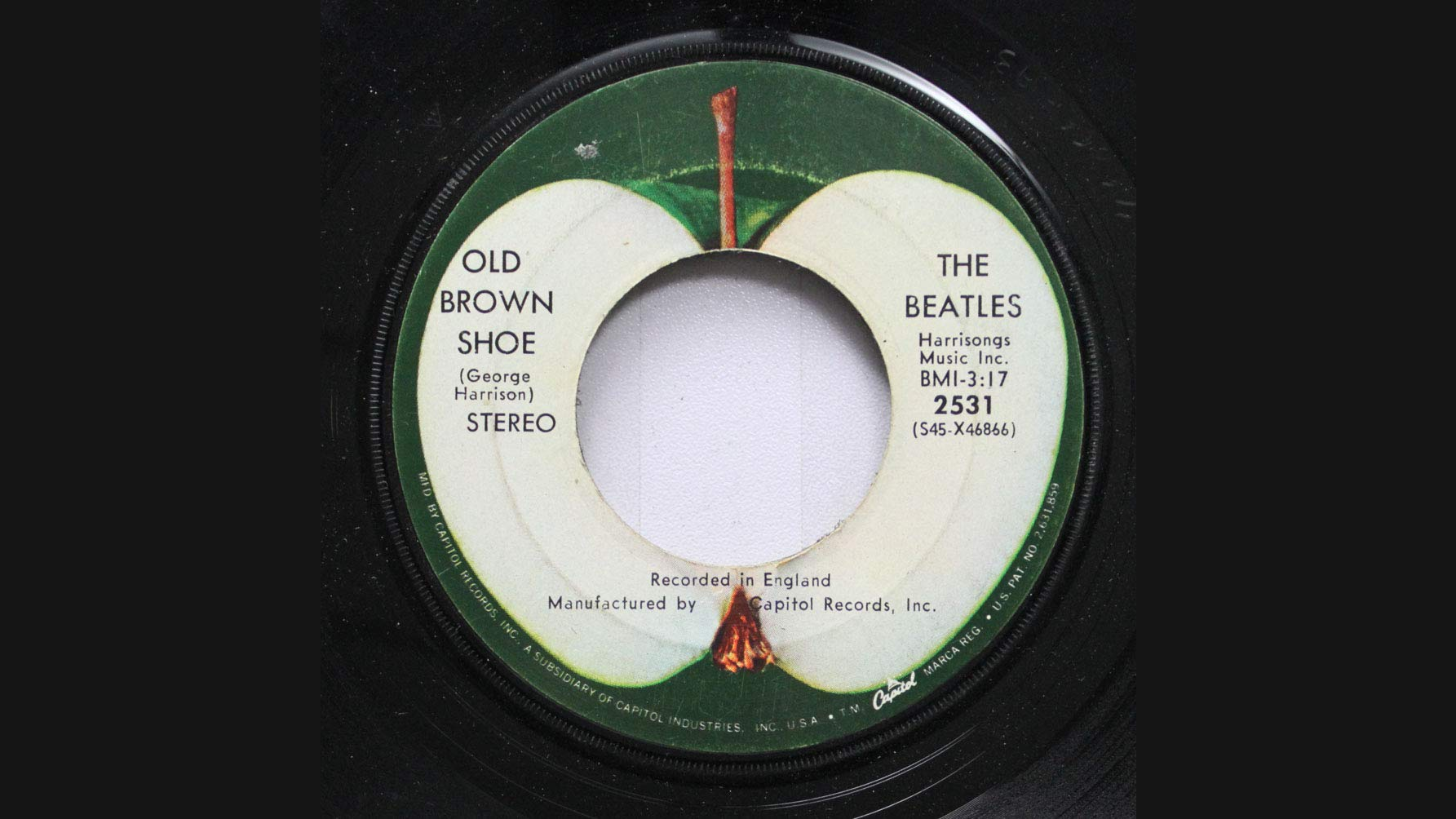

11. Old Brown Shoe

“Old Brown Shoe” exists as the sonic blueprint for Harrison’s post-Beatles liberation. “Old Brown Shoe” was initially recorded as a solo demo before the full band version, featuring complex chord changes and a distinctive bass line (which Harrison played himself) that demonstrated his growing confidence in challenging the Lennon-McCartney duopoly. “Old Brown Shoe” became a musical declaration of independence, relegated to B-side status only because it threatened the carefully constructed band hierarchy.

John Lennon’s advocacy for releasing “Old Brown Shoe” as an A-side reveals the internal power struggles hidden beneath the Beatles’ harmonious public image. Harrison’s increasing prominence foreshadowed the band’s inevitable dissolution, much like watching a supporting actor outgrow their script. The lyrics about opposites and duality in “Old Brown Shoe” perfectly mirrored Harrison’s position: simultaneously essential to the Beatles’ sound while being marginalized in the broader narrative pushed by music media and management.

10. Tell Me What You See

“Tell Me What You See” represents the Beatles’ most efficient creative exercise – it was recorded in just four takes over two hours in February 1965. Originally considered for the “Help!” film before being rejected, “Tell Me What You See” features an unusual instrumental lineup, with George Harrison abandoning his guitar to play the güiro—a Latin American percussion instrument that added texture that most British bands wouldn’t have considered.

The track “Tell Me What You See” reflects how thoroughly the music industry has sanitized Beatles history, erasing their global musical influences in favor of a more marketable “British Invasion” narrative. Like finding out your favorite childhood superhero had powers the cartoons never showed, discovering their percussion experiments reveals a band far more musically adventurous than the oldies stations would have you believe. The song serves as evidence of the Beatles’ musical curiosity, which extended far beyond the boundaries of Western pop.

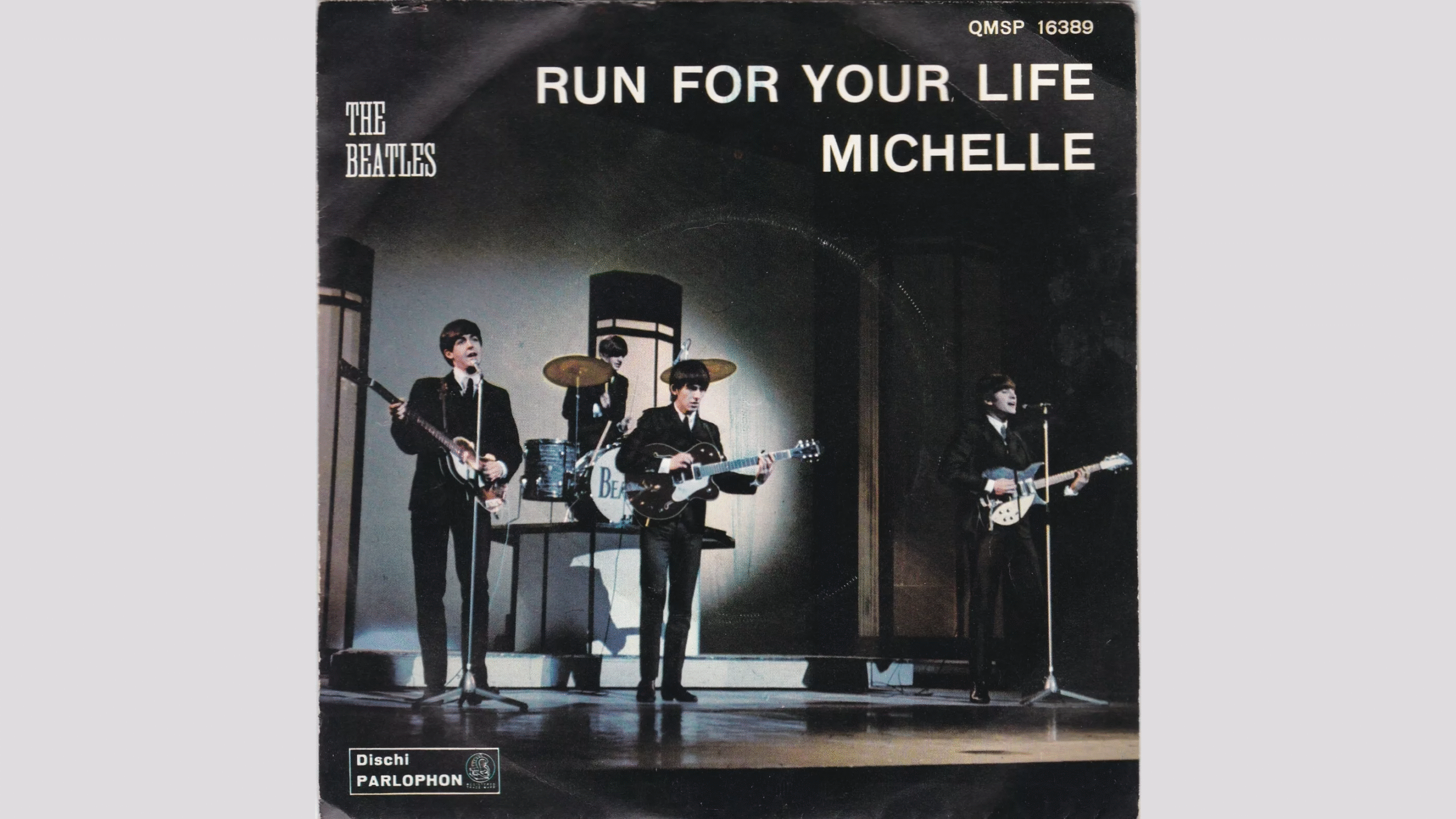

9. Run for Your Life

“Run for Your Life” serves as the uncomfortable footnote in Beatles mythology – it presents the skeleton in Lennon’s closet that contradicts his later image of peace and love. Lifting its opening line directly from Elvis Presley’s 1955 “Baby Let’s Play House,” “Run for Your Life” encapsulates the casual misogyny embedded in early rock music. Lennon later called it his least favorite Beatles track, while Harrison reportedly enjoyed playing on it – a tension that exposes the complex personalities behind the unified band image.

The song “Run for Your Life” plays like finding an offensive early tweet from someone now positioned as a cultural saint. Its threatening lyrics about jealousy and possessiveness have aged as poorly as milk left in the Desert, becoming increasingly problematic as cultural attitudes have evolved. The track sits uncomfortably at the end of the UK’s “Rubber Soul” album, like an unwanted party guest, reminding listeners that rock’s rebellious image often masked regressive attitudes that the music industry was happy to profit from, while avoiding deeper examination.

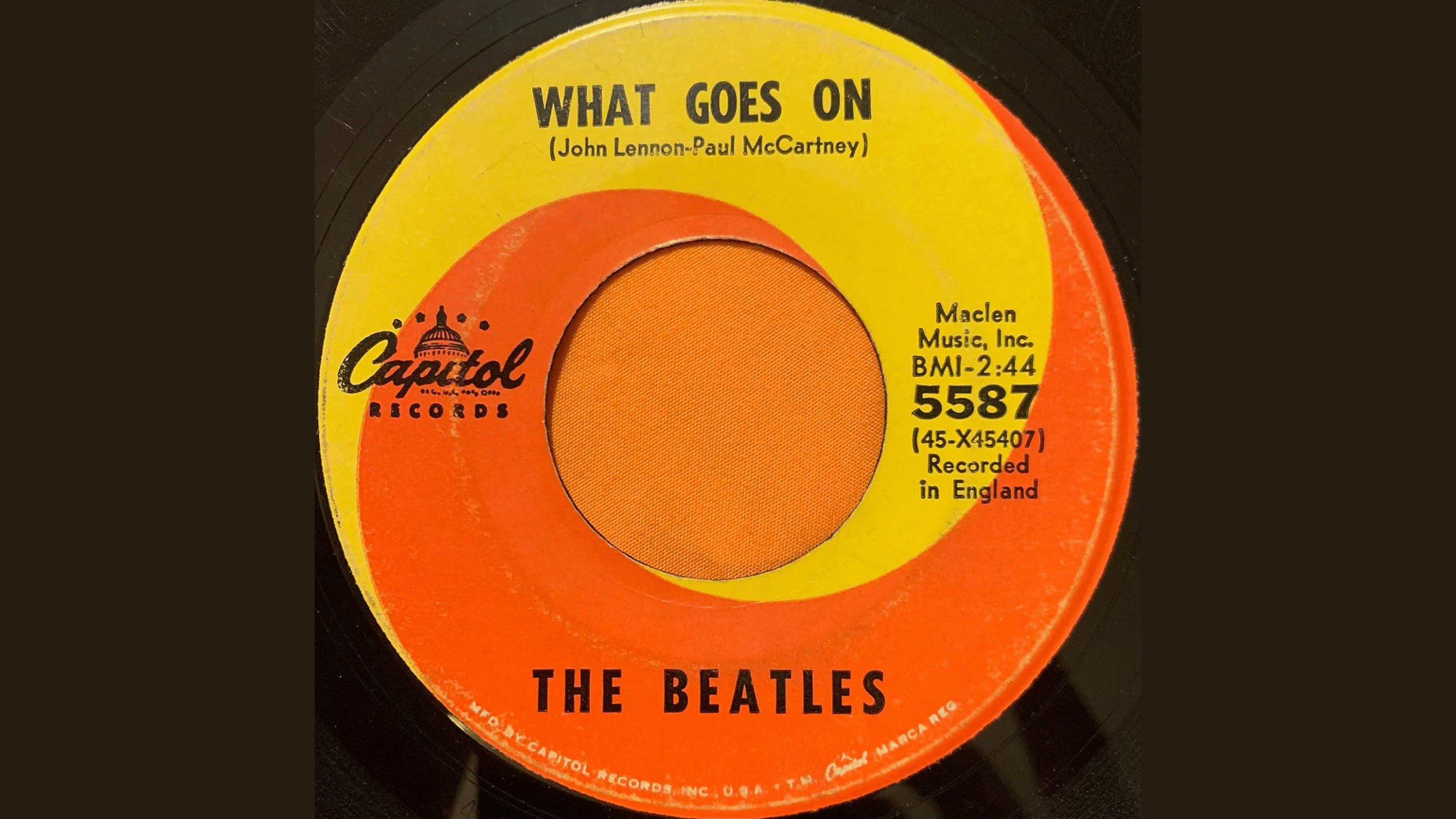

8. What Goes On

“What Goes On” stands as one of the rarest Beatles artifacts – it represents a true Lennon-McCartney-Starkey collaboration that proves Ringo’s creative input extended beyond his distinctive drumming. Originally demoed in 1963 but shelved for two years, “What Goes On” became a victim of record label geography when Capitol Records removed it from the American version of “Rubber Soul.” This continued the industry’s tradition of treating US audiences as if they couldn’t handle artistic complexity.

The track’s journey through release purgatory – “What Goes On” appearing as a B-side to “Nowhere Man” before finally landing on “Yesterday and Today” – mirrors Ringo’s own status within music journalism: perpetually repositioned to serve others’ narratives. This country-western flavored oddity showcases the band’s genre experimentation years before their more celebrated psychedelic period. The song exists as proof that the Beatles were musical shapeshifters long before they grew their hair long and discovered sitars.

7. Maxwell’s Silver Hammer

“Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” stands as the musical equivalent of a family argument that erupts at Thanksgiving dinner. “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” showcases McCartney’s music hall style about a hammer-wielding medical student murderer who created recording session tension bordering on mutiny. Lennon refused to participate after becoming ill, while Harrison and Starr openly rebelled against McCartney’s perfectionism. Ringo’s assessment of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” was blunt: “the worst session ever!“

The cheerful melody of “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” masking dark lyrics about serial killing perfectly encapsulates McCartney’s artistic duality – the cute Beatle with the twisted imagination. Like watching a Wes Anderson film about a gruesome crime, “Maxwell’s Silver Hammer” challenges listeners to reconcile its charming exterior with its disturbing content. The track’s divisive reception within the band foreshadowed their impending breakup, proving that even musical geniuses have limits to their collaborative tolerance.

6. Little Child

Facing a looming album deadline with limited material, Lennon and McCartney hastily crafted “Little Child” as filler after Ringo refused to sing it, exposing the unglamorous reality behind the Beatles’ mythologized creative process. “Little Child” was a work song written specifically to fill out the Beatles’ second album in 1963. Originally intended for Ringo, his refusal to sing “Little Child” forced Lennon and McCartney to handle vocal duties instead. This behind-the-scenes negotiation exposes how band dynamics operated when the cameras weren’t rolling and the recording light wasn’t on.

The bluesy arrangement of “Little Child,” with Lennon’s harmonica playing, revealed their rhythm and blues influences, which music historians often downplay to maintain the narrative of the Beatles as pop innovators rather than skilled interpreters of American musical traditions. Like finding out your favorite restaurant’s signature dish started as a way to use up leftover ingredients, “Little Child” reveals the pragmatic reality behind the mythologized creative process – sometimes great art emerges not from divine inspiration but from meeting a deadline with whatever you have.

5. The Long and Winding Road

“The Long and Winding Road” transformed from McCartney’s intimate piano ballad into the unwitting centerpiece of the Beatles’ bitter end. “The Long and Winding Road” was released as a single in America but not the UK, becoming a hit despite – or perhaps because of – Phil Spector’s unauthorized orchestral arrangements added during post-production. McCartney’s fury at these additions to “The Long and Winding Road” without his approval marked the final betrayal in the band’s fractured partnership.

The song “The Long and Winding Road” became the Beatles’ last number one in America while simultaneously representing everything wrong with the music industry’s approach to art – executives making creative decisions without artist consent (The Beatles’ 64 documentary also details how the band debuts in the US). Like a beautiful painting that someone else decided needed more color, Spector’s wall-of-sound production buried McCartney’s original vision beneath layers of strings and choir vocals. The track requires a specific emotional state from listeners – contemplative melancholy isn’t background music for grocery shopping or gym workouts, limiting its versatility compared to other Beatles classics.

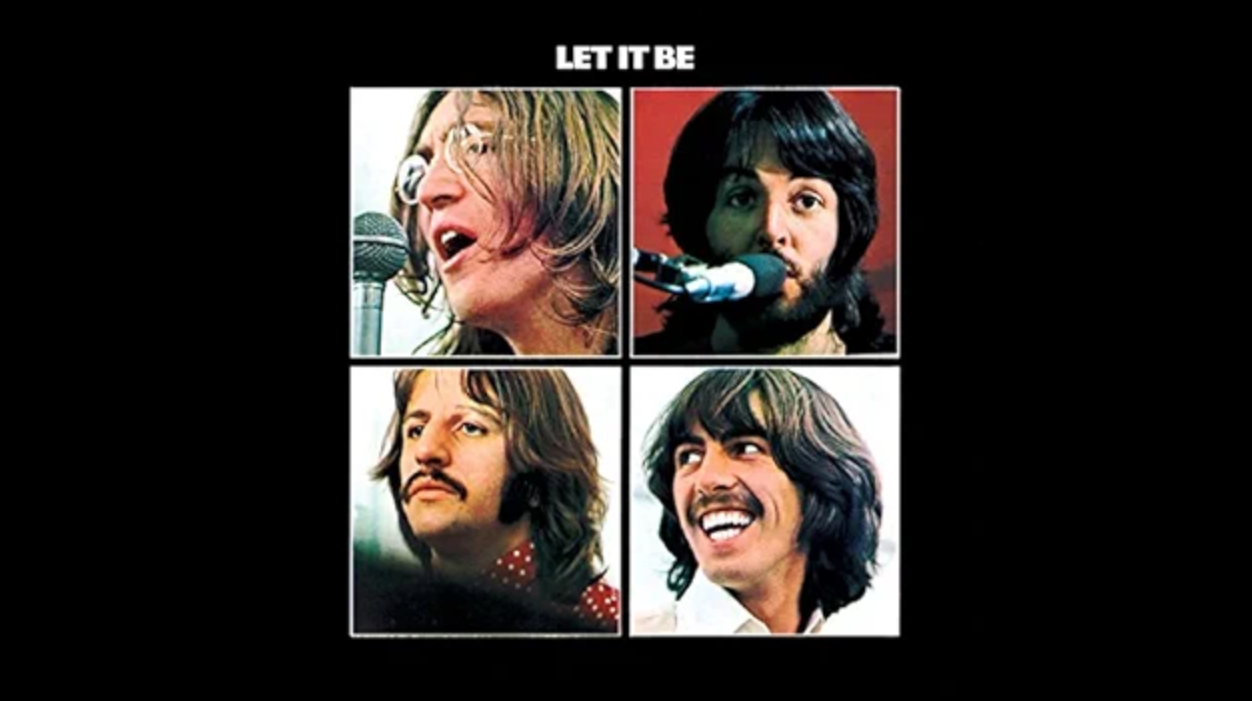

4. Dig It

“Dig It” captures the Beatles at their most unfiltered – “Dig It” represents a jam session trimmed from over four minutes down to barely sixty seconds on the “Let It Be” album. The aggressive editing of “Dig It” suggests collective disinterest from everyone except Lennon, whose freestyle vocals and random shout-outs provide the only memorable elements. The final version of “Dig It” represents a band barely functioning as a cohesive unit, each member mentally halfway out the door.

The abbreviated track of “Dig It” offers a voyeuristic glimpse into the Beatles’ unpolished studio interactions during their final days. Like finding the raw footage that was cut from a classic film, “Dig It” shows the messy reality behind the carefully constructed Beatles mythology. The song’s preservation, even in truncated form, speaks to the completist mentality of rock historians – documenting even the band’s creative dead ends to maintain the illusion of musical infallibility that drives merchandise sales decades after their breakup.

3. Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da

“Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” exists as both a worldwide hit and a band-destroying irritant. “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” required perfectionism during recording sessions that pushed his bandmates to the breaking point, with Lennon particularly vocal about his hatred for the song. “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” incorporated ska and reggae influences before these styles became mainstream in Western pop, telling a simple story through an infectious melody that proved impossible to forget, much to Lennon’s apparent dismay.

The recording saga of “Ob-La-Di, Ob-La-Da” perfectly encapsulates the creative tension that simultaneously fueled the Beatles’ innovation and accelerated their dissolution. Like a relationship where the qualities you initially found charming become unbearable over time, McCartney’s meticulous attention to detail had transformed from a band asset to a collaborative liability. The track’s commercial success despite internal resistance demonstrated the growing disconnect between what audiences wanted and what the individual Beatles needed artistically – a gap that would ultimately prove unbridgeable.

2. Blue Jay Way

“Blue Jay Way” emerges as pure George Harrison – “Blue Jay Way” creates a fog-shrouded psychedelic journey so distinctively odd that producer George Martin reportedly couldn’t believe he had produced it. Written during a long wait for friends in the Hollywood Hills, “Blue Jay Way” features a disorienting atmosphere and unusual production techniques that frequently caused casual listeners to skip it when playing “Magical Mystery Tour.”

The track “Blue Jay Way” showcases Harrison’s willingness to explore sonic territories that challenged mainstream sensibilities. Like a David Lynch film that divides audiences between those who appreciate its dreamlike atmosphere and those who demand conventional storytelling, “Blue Jay Way” requires listeners to surrender to its hypnotic repetition and atmospheric discomfort. The song’s cult following among psychedelic enthusiasts demonstrates how alternative music communities often form around the exact material that commercial radio rejected, creating parallel canons that exist outside official music industry narratives.

1. Yellow Submarine

Suppose you’re a rock purist who dismisses “Yellow Submarine” as childish fluff. In that case, you’re missing how this cultural phenomenon turned a simple Ringo vocal into a multimedia empire that still introduces new generations to The Beatles. “Yellow Submarine” features Ringo on lead vocals and innovative sound effects throughout, as this seemingly simple sing-along topped UK charts as part of a double A-side with “Eleanor Rigby” – a pairing that perfectly embodied the band’s commercial/artistic duality. “Yellow Submarine” later inspired an animated film, extending its cultural reach beyond music into visual media.

The track “Yellow Submarine” reveals the Beatles’ understanding of audience segmentation long before marketing departments had coined the term. Like a Pixar film that works on different levels for children and adults, “Yellow Submarine” provides an entry point for young listeners while maintaining enough studio innovation to reward close attention. The dismissal by rock purists of “Yellow Submarine” highlights music criticism’s persistent bias against accessibility, as if artistic merit correlates directly with difficulty rather than effective communication across generational divides. If you enjoyed this list of the least liked Beatles songs, then you might be curious to find out these prominent artists who aren’t fans of their music.